An Unorthodox Union

It was 1968. On university campuses, the Beatles blared from dorm-room stereos, and VW Beetles infested parking lots. The times were a-changing, and they were ripe for bold initiatives.

Few initiatives are as bold as an unorthodox marriage—especially in the halls of academia. So it was a bit of a maverick master stroke when two eminent scientific institutions—the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution—announced in 1968 that they had agreed to create a joint program for graduate studies in oceanography.

At first blush, the union seemed made in heaven. MIT was the foremost American center of higher education in science and engineering, but it did not offer a full range of ocean sciences and was threatened with becoming literally and figuratively landlocked from an exciting, important, and rapidly emerging field of science. WHOI, on the other hand, literally and figuratively faced the sea, launching research ships and ocean expeditions from its active port in Woods Hole. But it had no shore-based provisions for teaching fundamental science courses and spawning new generations of oceanographers to continue seagoing research.

“Woods Hole had a vast laboratory, which was the ocean,” said Howard W. Johnson, who was president of MIT in 1968. “We had the classrooms and the students who were interested in that laboratory. So the connection was natural.”

But if the idea made so much common sense, why hadn’t it been done before? The primary reason was that, well, it had never been done before. It was an unprecedented venture in higher education for two highly successful, fiercely independent institutions to join together, especially ones with such different upbringings.

Many scientists at WHOI preferred to conduct their high-seas research without the burdens of teaching and advising students or the constraints imposed by academic bureaucracy, committees, and rules. MIT faculty members had their own qualms. For starters, the idea of sharing its prestigious degree with another institution was new and not something to be entered into lightly. In addition, some academic curmudgeons deemed the young science of oceanography a playground for yachtsmen or a bastard science unworthy of the same degree given to students of more classical fields like physics, biology, and chemistry.

A match made in academia

To stem the hemming and hawing and bring MIT and WHOI to the altar required the strong intervention of visionary matchmakers. Among them were Frank Press, head of MIT’s Earth Science Department, who had made several cruises on WHOI’s research ship Atlantis and knew the value of an integrated approach to the earth sciences that included land and oceans. At WHOI, Director Paul Fye rounded up support for the partnership among trustees and gathered funds from private donors to ensure that WHOI could hold up its end financially. J. Seward Johnson gave two gifts totaling $8 million, and Mr. and Mrs. W. Van Alan Clark donated another $5.25 million to launch the new education program.

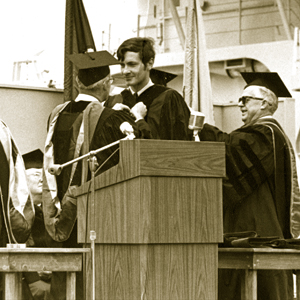

With this dowry promised and a nuptial agreement hammered out, WHOI and MIT were formally wed on May 8, 1968, at a signing ceremony aboard WHOI’s research vessel Chain. The memorandum of agreement joined MIT and WHOI “in a cooperative arrangement in which each institution … will participate as an equal partner.”

This was no merger or acquisition, but a marriage—one that is still going strong after 40 years. In June 2008, the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography/Applied Ocean Science and Engineering awarded its 800th degree, said James Yoder, vice president for academic programs and dean at WHOI. “Many of our graduates are on the faculty at leading U.S. and international universities, research institutes, and colleges. Others work for companies involved in offshore petroleum exploration, are senior officers in the U.S. Navy, hold high positions in the federal government, work in private industry, or have founded their own successful companies.”

In 2004, an external review committee composed of elite scientists and educators from other institutions assessed the program and concluded: “The MIT-WHOI Joint Program remains a (if not the) top educational program covering all the marine sciences and engineering. The leading institutions of marine science around the world have significant representation of graduates of the JP on their staff. The vigour of the program is shown by the quality of students’ research and the very warm feelings they express for the Institutions and people that foster their development.”

Both institutions have profited from the relationship, and so have their offspring—the students. JP students take advantage of the complementary strengths and capabilities of two great institutions. They enjoy complementary campuses—one with all the rich cultural opportunities of an eclectic metropolis, the other full of physical beauty and small-town charm. They have access to the fundamental pillars of an oceanographic education and access to the sea, where they can get their hands dirty using cutting-edge tools and vehicles.

Having two great parents has its advantages.

Lonny Lippsett, Oceanus Magazine

MIT-WHOI Joint Program Memorandum Of Agreement- 1968

Related Files: